Another overdue blog about a very common problem that lands a lot of people in our office who have often been worked up medically and released with no good explanation or treatment plan.

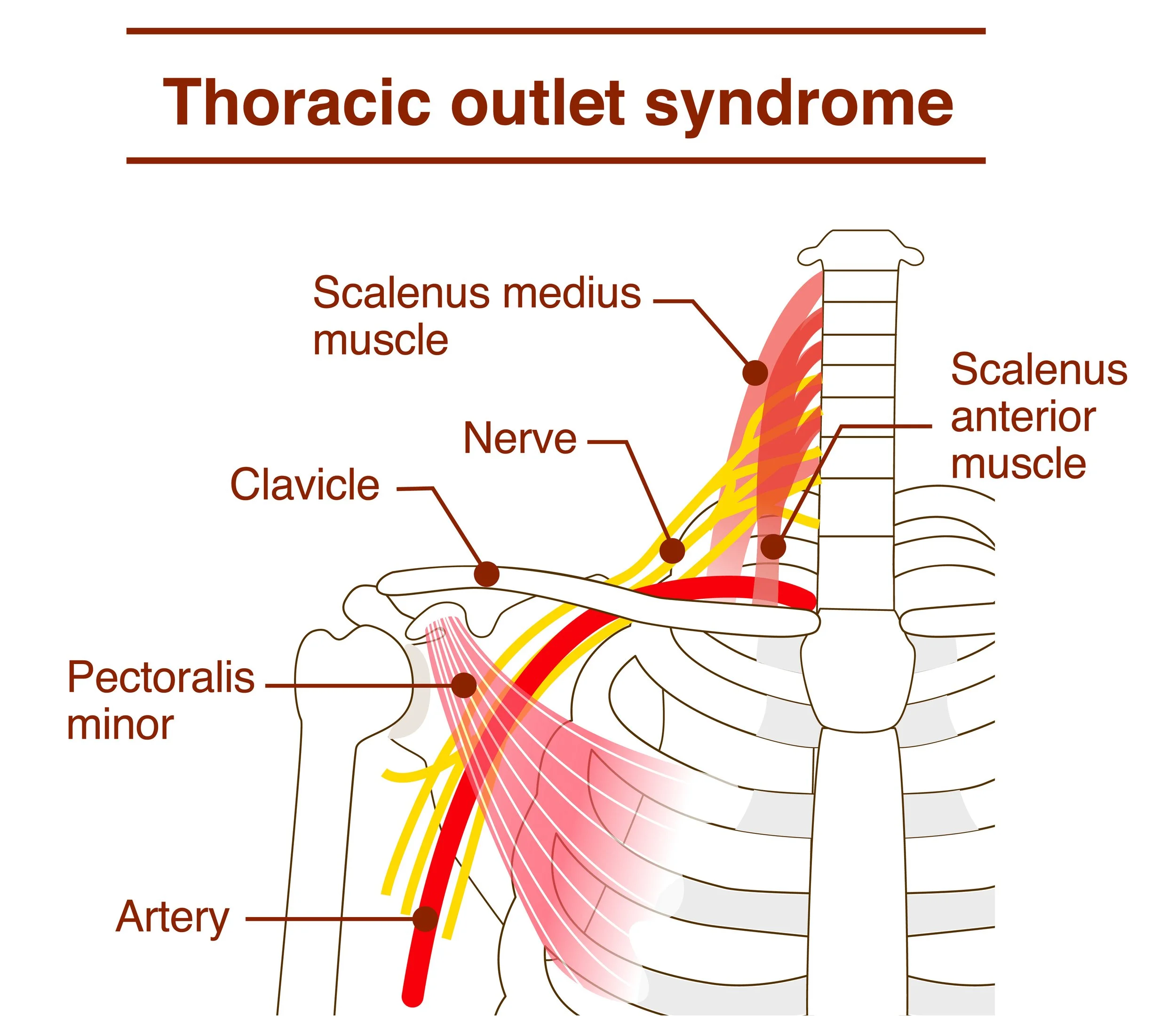

The term thoracic outlet syndrome is an umbrella term encompassing several clinical syndromes, which all have to do with compression of nerve and/or vascular structures between the neck and shoulder.

Once the cervical nerves exit the inter-vertebral foramen, a.k.a. the space or hole between two adjacent vertebrae, they will join and repackaged themselves in three branches that will then travel downward into the upper arm and give rise to the three major peripheral nerves: radial, median, and ulnar. Shortly after their redistribution from cervical nerve roots into peripheral branches, they are joined by nerves and arteries exiting from the thoracic cavity, to form the neurovascular bundle. You will often see the abbreviation NAV, to describe respectively nerve artery and vein, that travel together. As a result, any of these thoracic outlet compression syndrome subtypes will almost always include a combination of symptoms due to compression or irritation of the nerve as well as compression of vascular structures. As a result, the symptoms can include not only pain, numbness, but also change in blood flow into the upper extremity that can manifest as sensation of cold and discoloration.

The most common causes of thoracic outlet syndrome is that I find myself treating in the today practices are as follow:

– the scalene muscles are really a big player. They respond to cervical injuries by going into spasm, or developing scar tissue from things like hyperextension whiplash injuries. The soft tissue injury to the scalenes will often result in strangling or adhesions to the neurovascular bundle and brachial plexus. It's relatively easily to palpate the problem if you know where to look and how much pressure to apply. If the scalenes are causing the thoracic outlet symptoms, you can reproduce it by lightly compressing the muscle into the neurovascular bundle. A normal interface of the scalenes with the brachial plexus will move out of the way and cause no symptoms with light to moderate pressure.

– Improper alignment of the anterior first rib to the posterior clavicle. This is often the result of upper thoracic sprains and or shoulder girdle sprains, especially a chronic clavicular and sternal clavicular injuries. After the neurovascular bundle and brachial plexus exit the scalenes they have to "dive" posterior and underneath the clavicle to enter the anterior axillary area.

– Deep pectoralis minor and coracoclavicular injuries or repetitive strain injuries. There's a pretty narrow space behind the pectoralis minor for the neurovascular bundle to travel. Most modern humans are very predisposed to compression in that area because of our poor posture, with our shoulders hunched forward and constantly internally rotated. As a result there is not a lot of margin for an additional minor injury to the shoulder such as falls, heavy pushing, and certain athletic injuries from trying to do push-ups or presses. I should say that seatbelt injuries from motor vehicle accidents are notorious for triggering new thoracic outlet symptoms and a lot of patients.

– Last but not least, the subscapularis muscle deep in the anterior superior armpit is also a common culprit. As the largest of the four rotator cuff muscles and a significant shoulder stabilizers, it sits just below and very close to the neurovascular bundle deep in the armpit. It's very easily triggered with falls and throwing injuries, as well as repetitive strain injuries.

Treatment of thoracic outlet syndrome needs to start with specific identification of the area of compression, and the structures causing the compression. For the most part the treatment plan is going to consist of a combination of cervical and thoracic alignments, a lot of very specific soft tissue releases to separate nerves and vascular structures from the compressing soft tissue, and addressing some of the chronic postural distortion patterns that predispose to the compression in the first place. But treating thoracic outlet syndrome can be surprisingly rewarding, since many cases do respond pretty quickly within a few treatments, partially because many of the structures are not usually associated with more complex long-term degenerative changes that are slower to respond to conservative care.